If we are not in a position to fascinate, then the audience loses interest

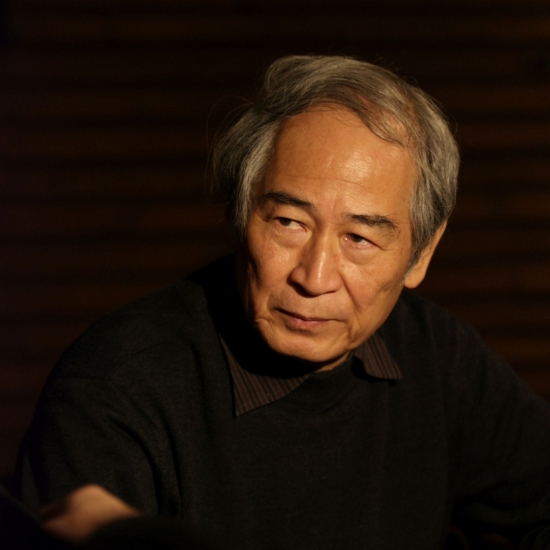

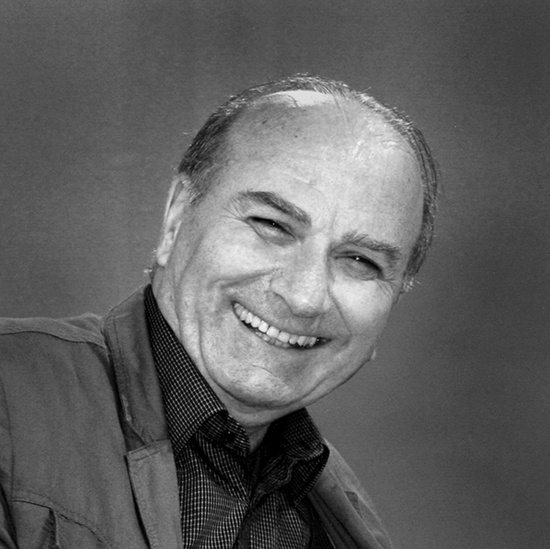

An excerpt from a conversation between Tadashi Suzuki and Theodoros Terzopoulos, which took place during the first Theatre Olympics focused around Greek tragedy.

Tadashi Suzuki: When we first met, Theodore, here at Delphi, I got the feeling that we have a lot in common. Not only because you're an artist, but also because I saw a man dedicated to enhancing our cultural and spiritual life by cultivating friendship and cooperation among artists. I immediately felt that, as an artist, beyond seeking recognition of your work, you are a fighter for the ideal of cooperation, you have vision and, in other words, you’re a great person.

Theodoros Terzopoulos: Well, Tadashi, that’s exactly how I felt. I had that nostalgic feeling of us having met somewhere sometime in the past. I guess this was mainly intuitive. After our first meeting I had the strong desire to work with you. And then, when I saw your work, I was overwhelmed. Overwhelmed by your method, the Suzuki method of stage direction.

Although I had never directly been taught the Suzuki method, when I saw your work, I felt your approach was entirely comprehensible. For in many aspects it corresponds to my own ideas. I had the feeling that I was literally watching my alter ego, and that there was striking affinity with Suzuki, the artist, as well as the man. “With this man I’ll really be able to work together as a friend”, I thought at once. And now, with the Theatre Olympics, this dream has finally come true! […]

When you, let’s say, Tadashi, stage an ancient Greek tragedy, and set it in our modern times, you require of the viewer something very important: his power of thought. I have the impression that your characters on stage do not have some special characteristic, but are more or less abstracts beings. That’s why the viewer’s imagination must be constantly aroused in a process of understanding the actor's psychology and his role. In other words, you require of the viewer the power to think for himself. On the other hand, the same applies to the actor. […]

As it is, one of the aims of the Theatre Olympics, which gather many imaginative artists from all over the world so that they may communicate and interact, is to stage Greek tragedy. […]. You bring to Greece timelessness, transcending the limits of any certain age – and that is what the Theatre Olympics are all about. We don’t want to turn the Olympics into yet another Theatre Festival. We want to try and see, whether and how it is at all possible to bring the text of an ancient Greek tragedy to life in a modern setting. […]

Tadashi Suzuki: We know that Europe has a long tradition in theatre. Japan, too, but Europe more so. Tradition, though, also means a lack of freedom. One is not free to do what one wants. Yet beyond this constraint inherent in tradition, there is the need to constantly review man in his modern surroundings. So I would like to ask you, what are the current trends in Europe with its tradition and what shape can theatre work take nowadays?

Theodoros Terzopoulos: That is a good question! To begin with, in Europe, theatrical expression differs from North to South. Greece, Italy, Spain and France included, southern Europe, that is, became the cradle of European culture, historically speaking. We, the Mediterranean peoples of Europe, have retained, in our daily lives, our bond with our ancient culture, or, at least, we try to. We also try not to lose touch with nature. Concepts like mountain, sea, sun, wind, are deeply rooted inside us. All of us southern Europeans have kept our cultural tradition alive in daily life. Our physical vitality bubbles over and makes us perceive things passionately and with alert sensibility. To a certain extent it seems that northern Europeans, as newcomers, are cooler and abide strictly by logic. This cultural difference marks ad expresses the differentiation in drama. We, for example, continue to include, even now, lyric or sensory elements stemming from ancient legends and songs, which we have heard from our fathers and grandfathers. Whereas in northern Europe, each country seems to be more inclined towards the technological aspect. Indeed, these countries show a clear trend towards technology, even in theatre. Quite often, artists of the theatre there don’t respond to simple things like sensation and emotion. They have, of course, perfected technique. Actors, overcome by proficiency, fall into its trap and lose the essential. That’s why we, southern Europeans, in spite of being part of Europe, have very much in common with Japanese theatre and Asian theatre in general. That’s what made me mention the affinity I feel towards your work.

Personally, when I refer to the theatre, I distinguish it as sensory versus logical. That doesn't mean, of course, that when we take up ancient drama or Greek tragedy in the Theatre Olympics we should discriminate between north European, south European or Japan drama. On the contrary, we should try to discern in each type of drama the common elements of material, subject or intrinsic spirit of the people. During the Theatre Olympics I would like us to review the way in which we express man’s internal world and the manner in which modern man perceives this. For example, regarding the interpretation of tragedy, there are people endowed with an expressive capacity of high aesthetic value, who have the power of carrying ancient tragedy over to the present day. And here, Tadashi, I would like to ask you: Don’t you think that truly great actors, regardless of their place of origin, are lately becoming very rare? It’s as though they’ve become subordinate to the settings and the music of a play, and their impact has dimmed. The Suzuki actors, on the other hand, have a marked presence. I believe that this is partly due to their tradition: What you bring us here is a great tradition of the Far East, the tradition of Noh and Kabuki, as seen from a contemporary point of view.

Tadashi Suzuki: What I felt when I came to Greece, as I looked at the text as theatre, what really amazed me, was the amount of human energy invested in its construction. Huge theatres were built with a capacity of five or ten thousand people, without the use of energy sources such as electricity, gas or oil, for pure entertainment. What I mean, is that this human energy must have been unique. This same type of energy fills the characters appearing in the text, who relate their feelings to others with passion and intensity. As I spoke with people of the theatre and seeing the theatres in Greece, these were the two points that struck me. I must say, though, that this used to be true in Japan, too. For both Noh and Kabuki, as types of drama, were “sources of energy”. The whole body was involved in expression. This was a cultural activity at the time. Yet, as you also said, Theodore, with the arrival of the movies and TV, as life started becoming easier, live energy has stopped being indispensable to man in his effort to communicate in a better way, to entertain himself, to understand his fellow man, to deepen his perception. I know these are the advances of our civilization, yet in the sense we mentioned, there has certainly been a cultural disintegration. This resulted in a weakening of drama and, consequently, great actors are actually becoming rare. And even though I believe that an actor is the guardian of fundamental elements of cultural activity, I agree with you, Theodore, that this kind of actor is almost extinct. That's why we must produce again – as may have been the case also with Greek drama, Noh and Kabuki – that kind human energy which confirms human existence and entertains.

Theodoros Terzopoulos: I have the same view. Besides, with the opening of the Theatre Olympics, one of the subjects we will address, is how we can regenerate human energy. What we do nowadays, is lie on a couch in front of the TV, and whenever a problem arises, we ponder over it sitting on a chair, and that means that there is a decrease in energy emanating form interaction with others. One of the aims of the Theatre Olympics is to draw this type of man out of his shell, make him celebrate and be his springing board. So, we need energy from the participants, not lethargy! We must find ways to multiply places and occasions of human interaction and mutual influence.

Tadashi Suzuki: Man has ceased intriguing us, and we, the people of the theatre, are called upon to be intrigued once more by man; it is imperative that we regain this force. We are also called upon to play an important part in redefining ways of stimulation, discovering surprise and reaching to the core of human existence. In any case, your ancestors, Theodore, 2,500 years ago managed to convey to the whole world their insight on human matters and emotions – the element of surprise – and I consider that to be an awesome achievement. […]

People who are involved with the theatre must necessarily be interesting. For the discovery of fascination is one of the conventions of the theatre. The text itself offers an analysis of man plus the element of surprise, but then a group of people takes over and shares these features with us. If we are not in a position to fascinate, then the audience loses interest. And even though a part of the culture of contemporary society has abandoned the use of live energy, people continue to surprise and to move us, and we discover that there still exist people, who really fascinate, and no one can determine the source of their charm. The fact that we can make such observations, means that, ultimately, our culture possess a luxury and it would be good to cultivate this luxury in Japan and increase it.

Delphi, 24 August 1995